Okay, I know I left off the last chapter as we were heading to the Vault, but before I get to that there’s more to clarify. Sorry if you were hoping for more vault detail, but it’s coming, I promise.

Thin white guy, 1989.

By the time David signed the Ryko deal, we’d chased him for the better part of a year; and what a year it was. Since late 1984 I’d been working for Rob Simonds, one of the Ryko partners. He’d gotten me out of the tedium of Hartford Connecticut and into Minneapolis where we opened a loose chain of CD-only stores; two in the Twin Cities, another in San Francisco and another in Boston (this one was co-owned by Ryko President Don Rose). I’d worked at Rob’s distribution company, EastSide once the stores got rolling, where I am proud to say that, thanks to my buying savvy, we were the only account in the entire United States to never return a copy of the Bruce Springsteen Live Box Set – although one copy sat in our warehouse for over a year (opened!) before some poor sap bought it. On the other hand, I drastically under-ordered U2’s Unforgettable Fire, so it wasn’t all home runs.

Billboard magazine article on the newly opened CD Establishment store I ran. Rykodisc mentioned peripherally as one of many things Rob Simonds did at the time. Later, we made up our own fake Billboard alliterative headlines. There was a great one about Jimmy Buffet dying in a boating catastrophe.

In 1987, Simonds decided to start another CD-only label (ESD) to release smaller titles and I ran that for a while. We put out a bunch of great stuff (Residents, They Might Be Giants, Bruce Cockburn, a lot of Bomp! Records titles) and the label was profitable. The same year, Ryko hired me as a consultant. Don and Rob had frequently asked my opinion on the potential titles Ryko was considdering (I sold them on a Mission of Burma CD, you’re welcome!) and they were kind enough to formalize the relationship by paying me for my opinion.

This is the one of the earliest ESD logos as it appeared on the back of the first TMBG album. We later adopted the more famous ESD "guy" logo, which was a silhouette I'd lifted from some clip art.

That summer, we got word the Bowie RCA catalog was available and the parties started to feel each other out. Could Ryko swing that kind of advance? Would Bowie buy into our vision of the re-releases? Did he even know who the hell we were? By fall there was some real hope we were in the running and in January of 1988, I started at Ryko full-time. My first assignment was to write a proposal for the Bowie catalog, which was completed and delivered in less than a month.

Amazingly, I still have a copy of the finished proposal, a surprisingly simple, unassuming document. Mine is marked up with additional notes, some of which I need to decipher.

My original copy of the proposal. I think the scrawlings at the top were references to the various dbase files I created while cataloging the vault.

A quick side-note: In the course of researching a Bowie-related lawsuit years ago, I came across a copy of the original contract in my archives, hand-signed by Bowie. Ryko sometimes copied relevant departments on contracts, mostly so the heads of those departments could refer to them for deal parameters without having to consult with the Business Affairs team. This was helpful in budgeting, licensing, permissions, etc. I vaguely recall getting it at the time. I’m sure someone meant to send a photocopy, but instead I had an original – and I’m glad I do.

The proposal (optimistically) shows a very different campaign than the one that actually ensued. We had the first release, “a 3 CD, 5 LP retrospective set comparable to Bob Dylan’s Biograph” pegged for September 1988, followed by a CDV/CD single of “Little Drummer Boy / Peace On Earth” in December for the holidays. In 1989, a new album with bonus tracks and an accompanying CD single and CDV for each album, all sold separately, and each with unique content.

This presented some issues; there wasn’t an obvious video component for each album and honestly, it seemed greedy to force fans to buy three products for each release if they wanted to get all the material. It ran contrary to the philosophy of not exploiting the fanbase with unnecessary product, a philosophy we’d sold to Bowie by eliminating the extraneous compilations. This was by far the biggest deal Ryko had ever contemplated entering into, so perhaps those extra items may have been a fiscal safety net in order to maximize the catalog (and recoup a historically large advance). No doubt some fans would’ve loved little CD replicas of their 7” Bowie singles. On the other hand, with the CDV format abandoned by the end of the decade, those little guys might’ve generated some ill will – although many of the CDVs that were released are now highly valued collectibles.

What a stupid format.

Keep in mind we had not seen the Bowie archives at this point. We had no idea if Bowie would approve the release of every track we hoped to utilize, and some of them were only rumored to exist. Other known recordings were owned by third parties – meaning we would have to license BBC sessions or TV appearances, for instance. This isn’t impossible, but is time-consuming and the terms back then were particularly onerous. It’s amazing that any BBC recordings were legitimately released before the year 2000 – and I doubt anyone (barring Queen or the Beatles) who did license from them made anything in the bargain.

Also, the proposed monthly release schedule wasn’t based on any logic other than the calendar; ultimately it made more sense to group the albums together stylistically, but still chronologically. This gave buyers breathing room between titles to allow anticipation to build, and prevented Bowie-fatigue.

The initial proposal unimaginatively combined Changes 1 & 2 into a 2 CD set with other tracks. I recall opposing this idea, and luckily fate intervened, although we eventually released a two CD Best Of. It also bagged the Christianne F. soundtrack completely, along with the previously discussed extraneous RCA comps (Fame & Fashion and Golden Years).

This timeline would’ve been tough to maintain even if Bowie had signed the contract the day he got the proposal. The deal wasn’t signed until Spring of 1989, over a year later.

To be clear, I was not the only architect of this proposal, nor was I involved (except peripherally) in this the legal and financial aspects. My responsibility was the creative side, including the release plan. I began researching the catalog, hunting down tapes, bootlegs, fan publications and any books I could get my hands on.

Pre-internet, research was grinding it out; digging and getting your hands dirty. As a record collector, I had friends at some of the best Record Stores in the States, including the legendary Main Street Records in Northampton, MA and Mod Lang in Berkeley, CA. They helped immeasurably, supplying import books and oddball records. The most helpful Bowie book at that point was Dave Thompson’s excellent 1987 “Moonage Daydream”, which I used until it fell apart. There’s my original dog-eared copy below.

My bible for the better part of my research.

If the subjects of his books are any indication, Mr. Thompson and I share similar musical tastes (glam, early punk, hard rock, flamboyant rock, etc). Because I’m an enthusiastic reader of music books, I own A LOT of his books. As such, it was surprising when Thompson came after me in a Goldmine piece in 1990, calling the Sound + Vision series “the most disappointing reissue campaign ever.”

Keep in mind this was 1990 – there had barely been ANY single artist catalog-wide reissue campaigns at this point, and only the Beach Boys had added tracks or expanded artwork. The Stones had re-released their entire catalog with fanfare when they signed with Columbia / Sony, but nothing special product-wise; other than putting previously released albums on CD, this was hardly an exhaustive campaign.

Thompson’s “Hallo Spaceboy” book seems to back off of and revise his 1990 misgivings, but at the time it was really insulting, and, although it’s likely he didn’t know it at the time, Dave was writing from a place of misinformation and speculation. He actually references my response to the article he wrote bitching about the campaign, but neatly sidesteps the fact that he wrote the offending piece in the first place.

Long before we got the Bowie catalog I’d collected some Bowie vinyl bootlegs, including a few I’d bought used, without cover art. In an effort to keep their origins anonymous, most bootlegs were sold in plain white sleeves with printed inserts trapped under the shrinkwrap. A lot of the info on inserts was dubious if not downright wrong (or even missing), with incorrect song titles, recording locations, etc. This is hardly surprising considering the method by which the material was sourced. Thus, three of my Bowie boots had hand-written track lists on plain white sleeves, all scrawled by the previous owner, and, I assume, copied from the original (now lost) inserts. One of the better ones was a fantastic odds & ends collection of studio and live tracks. This eventually led to a mistake on my part, which Thompson called me on, but I’ll get to that later.

Another bootleg was a cassette of rehearsals for the Serious Moonlight tour in Dallas with Stevie Ray Vaughan on guitar. Coming on the heels of arguably his biggest breakthrough in the US, Bowie was not going to squander the opportunity by going “difficult” as he had after his mid-70’s run of hits, and the Serious Moonlight tour was an opportunity to be the Bowie his new fans wanted and expected. He not only revisited his best-known material, but showed the newbies how many great songs they’d missed on the underpromoted “Berlin” records. To be fair, the live versions were a few years removed from the cold sterility of the German studio and the shadow of minimalist Kraftwerk in which they’d been birthed. They hummed with warmth and, slightly rearranged, came on as the “hits that never were.” The setlist was a well-crafted, highly listenable summation of the more commercial aspects of the previous decade.

A weird pairing destined to not happen. Note the Dame is still nicotine addicted at this point.

Although Vaughan never played a single date, the subsequent tour stuck to that bootleg set list and was all the better for it. I saw the show in Hartford, CT and Bowie proved his point in a happy, upbeat performance, propelled largely by enthusiasm and rarely by gimmicks. The show and that rehearsal tape left lasting impressions.

Anyway, 1988-1989 negotiations went along with moments of high hopes, often quickly shattered. Don Rose & Arthur Mann (Ryko founder and the company’s lawyer) had met Bowie in Zurich for an initial get to know you lunch. I made a few trips to the Isolar offices in New York, where we met with various associates about our plans. Bowie was on board to add extra tracks, and he insisted the CDs be released at full price, not mid-price. This was not an issue for us - we had never imagined it any other way. Honestly, there were few, if any mid-price CDs in those days – at least in the US.

I’m not sure why the negotiations dragged on so long, but at least part of it was Tin Machine activity – although he had yet to inform any of us about the new band, or its forthcoming album. EMI must’ve been aware of Tin Machine at this point, as the album came out in May of 1989.

I assume it would’ve been easier for Bowie if one company handled his catalog worldwide. Most likely EMI would’ve fit the bill perfectly, but it was not to be. An illicitly-obtained EMI US projections list showed they VASTLY underestimated the catalog’s appeal – and had no plans beyond straight reissues. Also, it was rumored Bowie & EMI were on the outs after the post-Let’s Dance sales decline. EMI may have proposed cross-recouping Bowie’s catalog royalties against those from his new albums, which would’ve been a total non-starter for a guy with other options.

For whatever reason, EMI and Bowie could not see eye to eye and the deal successfully closed at Rykodisc. This was the second time EMI’s inability to grasp a catalog’s potential had served us well. In the earlier part of the decade, Zappa was distributed by EMI US. When we approached him about licensing his catalog for CD, he felt obligated to run it by his then-current label partner. They’d told Zappa no one would buy his catalog on CD and subsequently they had zero interest in releasing it. This put the Zappa catalog at Ryko, which led to Hendrix, which led to Bowie, etc, etc.

Hate his music, love the guy.

Rykodisc was a small label, but enough of a heavy hitter in North America to handle the Bowie catalog in that territory (and maybe even in parts of Asia), but while we had good partners in Europe, they were largely distributors, not marketers. They didn’t have the staff or expertise to mount a campaign of this magnitude, so we were not in a position to take on the catalog there. When the Bowie/Ryko contract was finally signed (in Spring of 1989, if I recall correctly), international rights were still up in the air and the first Tin Machine album was just about to drop.

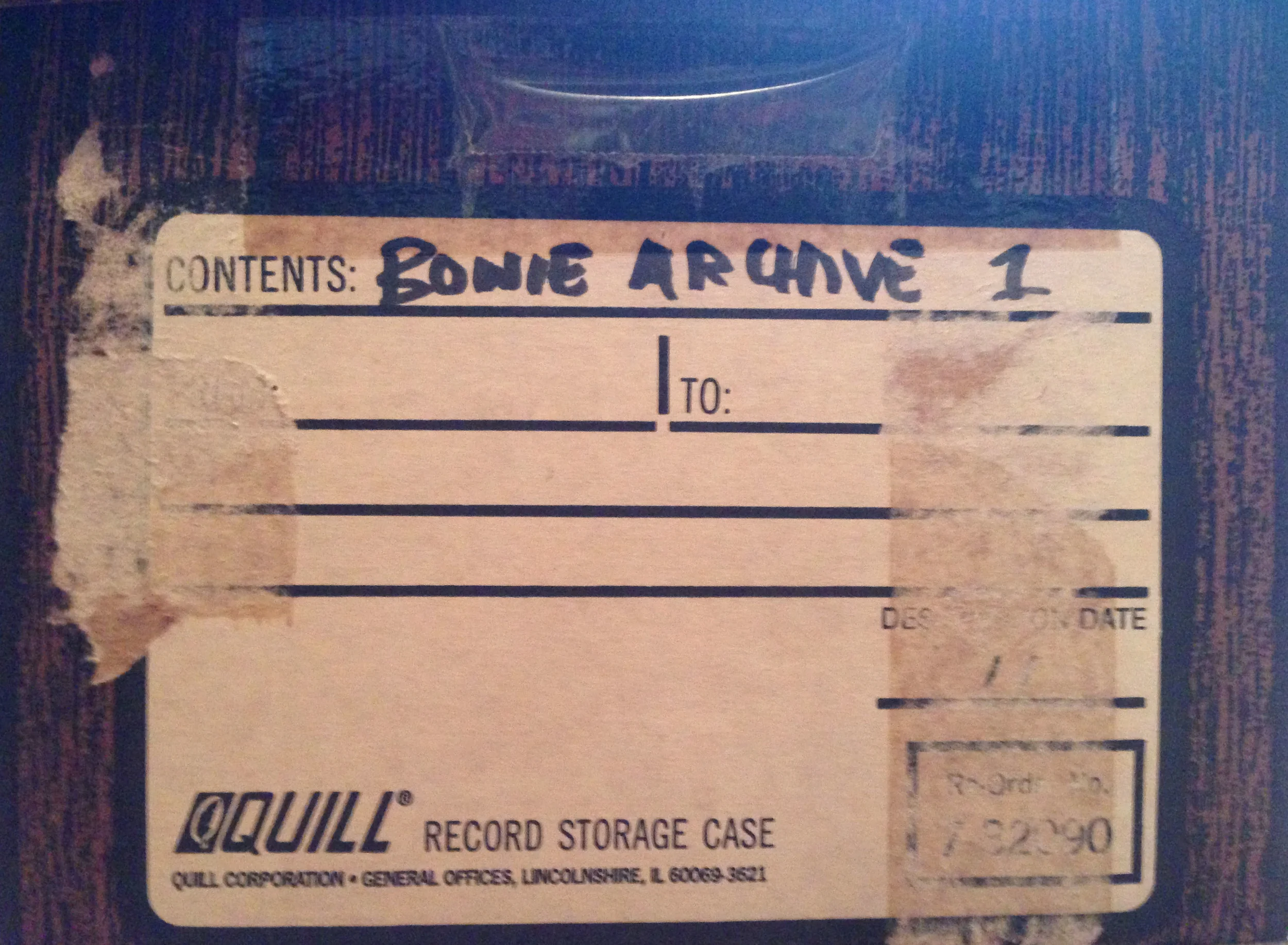

We had to hurry if we were going to get anything out in 1989, which was the plan. Bowie’s people at Isolar had sketchy cataloging of the vault, so we not only had to get our hands on the vault materials asap to see what was in there, we had to catalog all of it in the process.