Thanks for your patience & welcome back. I will have another post within a week – promise!

Here I want to finish up the cataloging process and in the next post I’ll get into the track selection choices for the box, and what Bowie and Ryko determined the purpose of the box to be, not what a handful of maroons have decided it is.

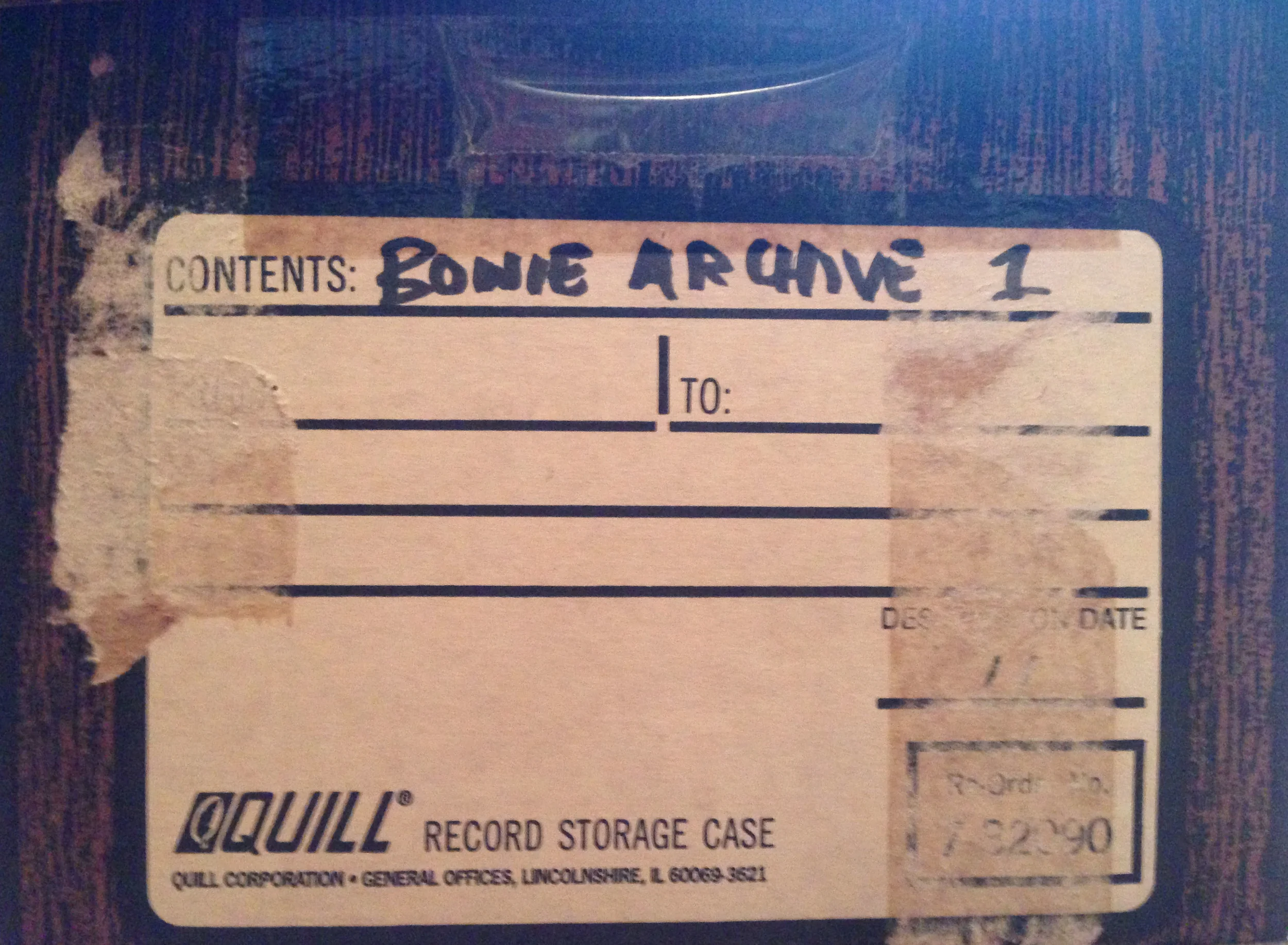

It’s the spring of 1989 and I’ve been pouring through the Bowie vault, cataloging everything. It became clearly unrealistic to think EVERY single item in the vault could (or even SHOULD) be cataloged.

For instance, there were numerous envelopes filled with re-re-reprints of RCA Promo Photos. Once I’d catalogued one print of a particular photo, I would put all the other copies in a file and list it as just “photos” or “multiple prints of such & such photo”. This saved a ton of time and kept me (relatively) sane.

There were hundreds of tapes in what seemed like just as many formats. There were two track ¼” tapes, 2” 16 track session recordings, large digital tapes that looked like giant betamax cassettes, cassettes, and more. They were in 12” reels, 7” reels, 5” reels, and augmented with 16mm tapes, VHS tapes and giant reels of video.

...so...many...tapes...

After I had catalogued each item, it was sent out to Dr Toby Mountain at Northeast Digital, who (along with his staff, including assistant and future mastering lab owner, Jonathan Winer) would transfer EVERYTHING from analog to digital. In this case, DAT –a relatively new, and now completely irrelevant, format. Because there were often multiple copies of tapes of each album, Toby and his team were taking copious notes as they ran the flat transfers. When one tape of Space Oddity sounded particularly good (or bad), they’d note this for future reference. If they found something that was particularly interesting or mis-labeled, that was annotated as well.

"i'm thinking of a stupid format no one wanted and that didn't work very well. Anyone?"

With rare exception, the tapes were labeled, but we had no idea if anyone had actually made sure the tape inside the box matched the description on the outside. So while I was cataloging, I started to get DATs back of every single scrap of recordings. There were a few moments of false hope, like when we found an album master labeled “The Metrobolist” - which we hoped was a lost album, but instead it was “The Man Who Sold The World” before it had the name we know it by today.

Some tapes were in very rough shape. The 2 inch 16-track unmixed masters for the “1980 Floor Show” were falling apart in our hands. Recording tape in the 70’s was a thin piece of plastic coated in ferric oxide, which electronically transcribed recordings with a very high level of fidelity. But, if improperly stored, the fragile tapes start to break down. The oxide loses hold of the plastic and starts to “shred”. It was terrifying to open a box and see little bits of dark tape fall out.

Typical 16 track machine.

There are sometimes ways to rescue these tapes. At the time, one of newest developments was baking the tapes. This is pretty much exactly what it sounds like. You have to very carefully put the failing tapes into an oven, and hope the shredding oxide cooks itself back onto the plastic. It sometimes works with great results. Other times, the materials are just too far gone and can’t be saved. Such was the case with “1980 Floor Show”.

On YouTube most of the time...

We made every effort to breathe life back into the 16 track masters for those, but they were lost. I seem to recall hearing that NBC had held them for years and were only released back to Bowie in the 80’s. It’s quite possible there are decent two track masters for the recording somewhere, but I have to assume the final mixdowns were mono, as stereo TV was not a thing at that point.

Anyway, surprises and more surprises turned up as the DATs arrived from Northeastern Digital. Toby’s crew was working quickly, doing flat transfers onto DAT from all the two tracks. For the multitracks they did quick mixes on the fly, some of which ended up being used, even when there were second attempts to mix them with more care – the earlier roughs just sounded better. They would send me a blue folder with a DAT in one packet and bound in copies of the covers of each tape box. And then I’d listen, making notes and comparing them with Toby’s.

It’s important to recall that Bowie and Tony DeFries had yet to fully break at this point. They were still sharing ownership (or at least participation in the profits) of all the records from Space Oddity to Station To Station. This changed after Bowie did his bond deal in the 90’s, at which point Bowie used the funds to buy DeFries out and was finally extricated from Tony and MainMan.

Tony & David in happier (?) times. I was so intimidated by legends of DeFries' ferocity that I kept a cropped version of this picture (encompassing just Tony's head and redonkulous afro) on my desk so that whenever he'd call, I could look at it and realize he was not someone I should feel intimidated by. It worked quite nicely.

In 1989, the relationship was still quite frosty and I’d bet neither had spoken to the other since the 70’s except through intermediaries. One thing no one in the public realized was that the vault we got was (essentially) Bowie & DeFries’ “joint vault” of all the records up to Station To Station but from that album on, all that was in the vault was the two-track masters of the material David had commercially released. There were no multi-tracks of Station To Station and beyond sessions, and virtually no extra tracks for any of those records. “David Live” was the last record in the vault that was represented with multi-tracks.

I believe Bowie was extricating himself from DeFries (for the first time) during the recording of Station To Station, so it’s likely any extra tracks (if they existed) were squirreled away from the Joint Vault, probably so DeFries wouldn’t place a claim on them. That may seem crazy, but there were good reasons for this, although I wouldn’t find out why until later. In the process of finding out, I probably cost David a bunch of money and nearly derailed the whole “bonus tracks” situation.

It’s also possible Bowie didn’t record a lot of extra material once he was in control of his own destiny. From what I’ve seen & read, Bowie’s initial success funded not only some very good artists but also a non-stop party, all under Tony’s Mainman banner.

Probably feeling his finances were being looked after, Bowie may have had a serious re-think about his spending once the expensive Diamond Dogs tour ended and the cracks in his relationship with DeFries started to show.

There were recordings missing from the early years, too, but in general I found much of what I was looking for in the vault. David gladly supplied some wonderful surprises, including the “Space Oddity” demo that starts off the box set – but he wouldn’t let us use any of the rest of that tape, which was similar in nature to the minimal take of Space Oddity, had nine (?) songs, and ran about an hour long. The tape has circulated as a bootleg called “The Beckenham Oddity” for many years (going back at least to 1987) although the quality wasn’t as good.

While I was worried about the missing later rarities, I couldn’t focus on that problem at that moment - I had a box to produce. Ryko wanted it out for the holiday season of 1989 to start recouping the advance, the biggest they’d ever paid. So I had to get a three CD track list together, come up with a stunning, revolutionary package, appease David Bowie and my bosses, but especially the fans – and I only had about a month to do it.